Mediation as a Test of a Good Construct

[T]he appropriate level of analysis is the highest level such that no lower level gives different predictions.

― Garrett Baker

One way to operationalize a ‘good’ latent construct is to check whether it mediates the relationship between its indicators and external variables. This idea of mediation as a key criterion shows up throughout psychometrics, including in predictive validity, measurement invariance, and genetic covariance structure modeling.

Predictive Validity

For a latent construct to be useful, it should account for the association between its indicators and external outcomes. That is, once we extract the factor that represents the construct, the remaining item-level information should add little or no incremental validity. Let’s look at specific examples.

Personality

Leveraging a more nuanced view of personality: Narrow characteristics predict and explain variance in life outcomes

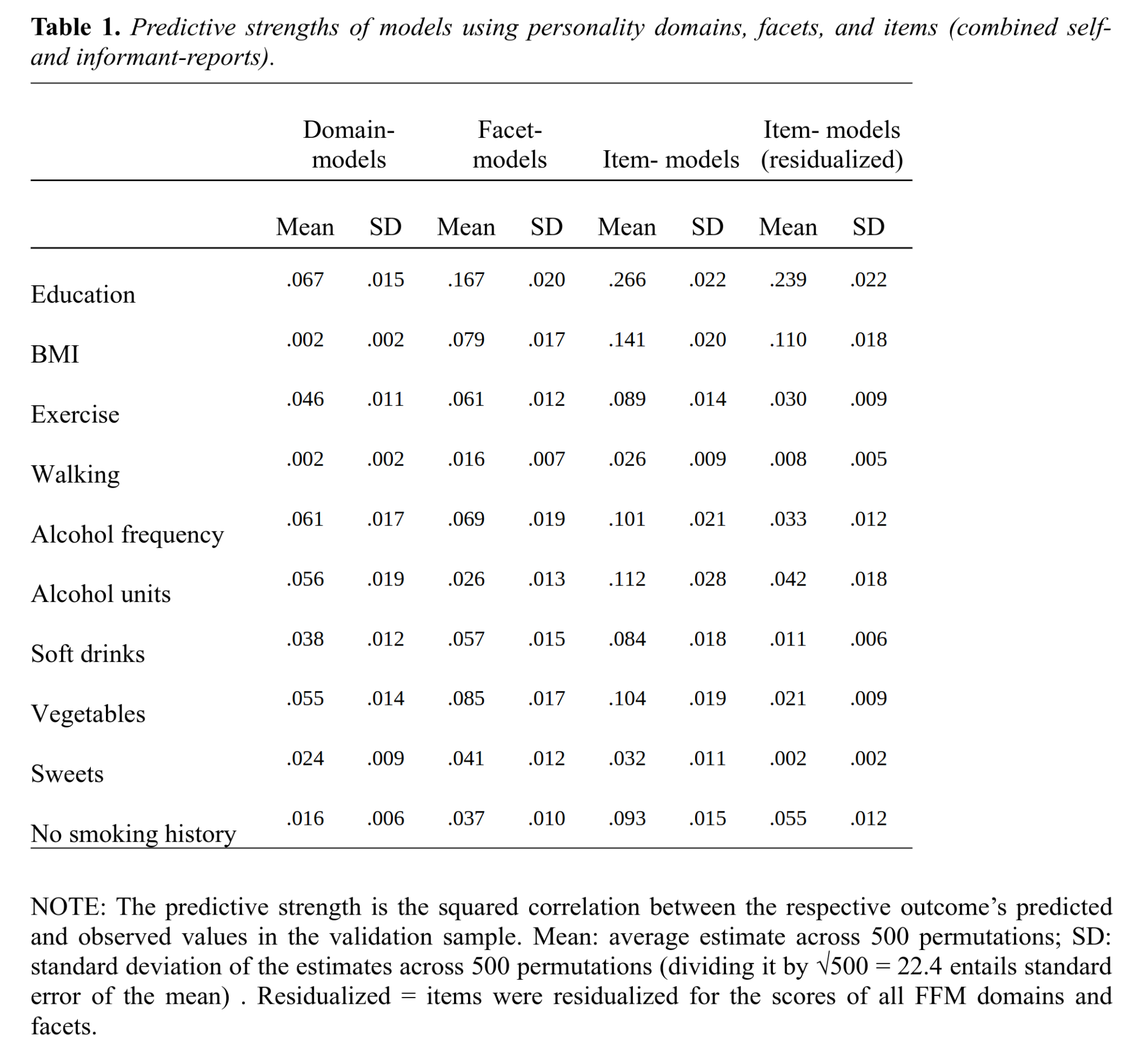

In the paper, Leveraging a more nuanced view of personality: Narrow characteristics predict and explain variance in life outcomes, the authors predicted 10 different outcomes (e.g., BMI, education, walking frequency) using three kinds of models: domain-based models (using only the 5 personality factors), facet-based models (using the 30 personality facets), and item-based models (using all individual items).

The median correlations1 between predicted and observed outcomes were 0.20 for domain-based models, 0.24 for facet-based models, and 0.31 for item-based models. The authors note that the success of item-based models “was not due to item-outcome overlap. Instead, personality-outcome associations are often driven by dozens of specific characteristics.” In other words, the questionnaire items provide substantial incremental validity beyond what is captured by the factors (or even the facets).

This suggests that the Big Five domains, as currently measured, are not unitary causal entities but instead aggregate partially distinct lower-level constructs. Because specific items explain variance in outcomes even after accounting for the domain-level factor, it does not make sense to treat the Big Five as unified psychological traits. (To be fair, psychologists do acknowledge the existence of facets beneath the domains, though this rarely affects their empirical practice.) As measured, the personality domains (along with their facets) function more as convenient statistical summaries than as coherent underlying traits.

Intelligence

Predicting training success: not much more than g

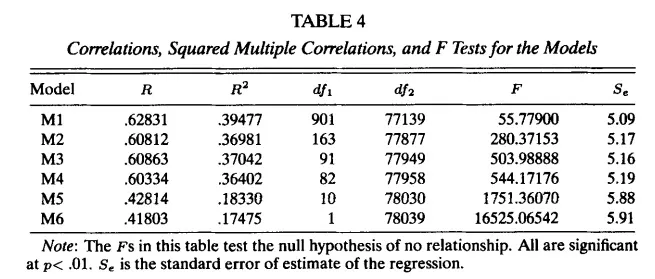

In the study, Predicting training success: not much more than g, the authors analyzed data from almost 80,000 people trained by the U.S. Air Force for various jobs to examine how well cognitive abilities predict training success. Everyone completed the ASVAB, ten principal components were extracted from the scores, and training outcomes were recorded. The results are shown in Table 4.

The relevant comparisons are Model 3 versus Model 4 and Model 5 versus Model 6. Models 3 and 4 included intercepts for each of the 82 jobs, since some jobs are harder than others. Model 4 used only the first principal component of the ASVAB (a proxy for g), whereas Model 3 used the first principal component together with the remaining nine components. The correlation between predicted and observed outcomes was 0.603 for Model 4 and 0.608 for Model 3. Using non-g cognitive scores therefore provided only a trivial improvement.

Models 5 and 6 did not include any job-specific information. Model 6 used only the first principal component (a proxy for g), while Model 5 used all ten components. The correlation between predicted and observed outcomes was 0.418 for Model 6 and 0.428 for Model 5. Again, the non-g components added very little predictive validity.

Clarifying the Structure of Intelligence

Now, it turns out that g doesn’t capture all the information in the indicators, even though it accounts for far more of the common variance than any other known psychological factor. Knowing whether someone performs better on verbal items or spatial items still helps predict, for example, which careers they’ll pursue, even after accounting for their level of g. For this reason, intelligence is best modeled with a hierarchical factor structure, with g at the top and group factors (e.g., verbal, spatial, memory) directly below. However, g is strong enough that simpler, non-hierarchical models often perform nearly as well in practice, as the study above shows.

Measurement Invariance

To ensure that a measure such as a questionnaire assesses the same construct in different groups, we need to test for measurement invariance. If measurement invariance holds, the measure functions the same way in each group, meaning the same construct is being assessed across groups. There are four levels of measurement invariance: configural invariance, metric invariance, scalar invariance, and residual invariance. For a more detailed explanation, I recommend 100 CI’s article, A casual but causal take on measurement invariance, which covers the topic from a causal perspective, but I will attempt to summarize the levels here.

Configural Invariance

Configural invariance means that the number of factors and the pattern of factor-indicator relationships are identical across groups. In other words, each group shows the same factor structure and the same indicators load on the same factors. If the factor structure differs between groups, configural invariance is violated. When it holds, the basic structure of the construct is similar across groups, which is a necessary starting point for comparing them.

Metric Invariance

Metric invariance means that the factor loadings for each indicator are the same across groups. In practical terms, the latent factor has the same influence on each item for members of each group. If the group variable alters the strength of the relationship between the factor and some items, metric invariance is violated. When metric invariance holds, the associations between the latent factor and the indicators are consistent across groups and we can compare latent variances and covariances.

Scalar Invariance

Scalar invariance means that, conditional on the same latent level, expected item scores are equal across groups. Violations occur when group membership predicts item responses even after conditioning on the latent trait. When scalar invariance holds, we can compare group means because differences in latent scores reflect differences in the latent trait rather than item bias.

Residual Invariance

Residual invariance means that for each item, the residual variance, which is the variance not explained by the common factors, is the same across groups. If the group variable affects the variability of the indicators, residual invariance is violated. When residual invariance holds, the scale for the latent construct is equally reliable across groups2, and the sources of between-group variation in the constructs being measured are a subset of the within-group sources of variation.

Examples

For concrete examples of the levels of measurement invariance, we can look at some of my earlier posts.

For configural invariance, consider the Kink Factor Analysis. Configural invariance is violated because the factor structure differs between cis men and women3. There is a different number of factors (9 for cis men and 14 for cis women), and even when factors appear similar, different items load onto them. For example, dominance-themed items loaded onto the cis men’s BDSM factor, while submission-themed items loaded onto the cis women’s BDSM factor.

For metric and scalar invariance, consider the Nerd Scale. When comparing loadings between groups, I found that item #15, “I have started writing a novel,” had substantially different loadings for men and women (higher for women). This means that nerdiness has a stronger effect on novel-writing for women than for men. To construct a measurement-invariant scale, the item should be removed, which I did for later analyses. When checking item biases by gender, several items showed bias. For example, item #19, “I have played a lot of video games,” indicates that even holding nerdiness constant, men are more likely to play video games. Including such an item would bias the scale, because at the same level of nerdiness, men would be more likely to endorse the item, making them appear nerdier than they are.

I don’t check residual invariance, and to be honest, most researchers don’t either.

Genetic Covariance Structure Modeling

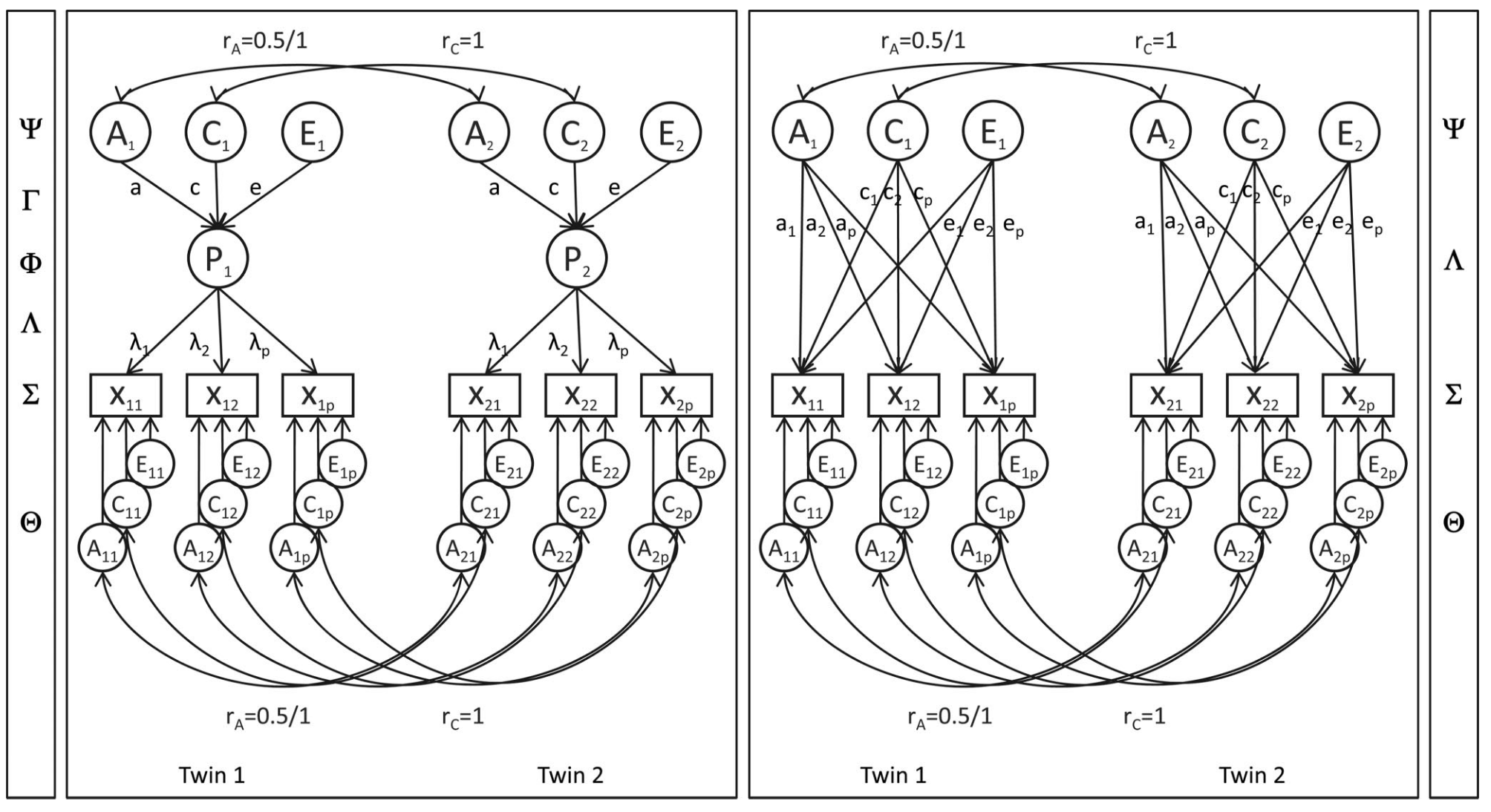

Genetic covariance modeling helps test whether the correlations among indicators arise from a single biological factor. In this framework, researchers typically compare two models: a common pathway model and an independent pathway model.

In the common pathway model, genetic and environmental influences on the indicators operate through the latent construct4. In the independent pathway model, genetic and environmental factors act directly on the indicators, and the latent factor is simply a convenient statistical summary of the indicators.

These models have very different implications. Evidence generally supports a common latent genetic pathway for cognitive ability, while personality traits such as Conscientiousness tend to fit the independent pathway model. This suggests that editing genes related to intelligence would primarily influence general cognitive ability5. In contrast, editing genes related to Conscientiousness is more uncertain, since such edits could affect self-discipline, prudence, or even social desirability bias rather than a single unified trait6.

Takeaways

Taking all of this into account, we can see why something like a general factor of athleticism is less ‘real’ than the general factor of intelligence. You can always extract a first principal component7, and athletic tests are usually positively correlated8, but several observations point in a different direction:

- Specific indicators, such as a 40-yard dash time, add substantial predictive ability beyond the athleticism factor when predicting external outcomes like performance in American football.

- Loadings and item biases vary by group variables such as sex. For example, women tend to be more flexible than men, while men tend to be stronger. Upper-body strength may also show differing loadings, such as a lower loading for women.

- An independent pathway model will almost always fit better than a common pathway model9. Genes that influence lung capacity do not usually influence hand-eye coordination, and there is no reason to expect all athletic traits to share a single biological pathway.

So even though you can extract the first principal component from athletic tests, it does not correspond to a single, unified biological mechanism in the way that g does.

Ultimately, arguably the most important aspect of mediation is that it is a core requirement of a reflective factor model, the kind discussed throughout this post. In reflective factor models, the latent construct should explain the shared variation among indicators such that any remaining covariation is negligible once the latent factor is held fixed. Without this property, the very idea of a coherent latent trait begins to lose its footing and psychometrics falls apart.

-

For an in-depth explanation as to why I prefer discussing results in terms of correlations instead of squared correlations, read Are we comparing apples or squared apples? The proportion of explained variance exaggerates differences between effects. ↩

-

Because measurement error and item-specific influences are comparable across groups. ↩

-

Apparently, some people don’t think the factor structure of kinks would differ based on sex, even though this should be obvious. In what world would it not? ↩

-

An important implication is that when different external variables affect the indicators only through the same latent variable, their effects on the items must be proportional. For any two such variables, A and C, the influence of A on a given item is a scalar multiple $k$ of the influence of C on that item, and this same $k$ applies to all items that depend on that latent factor. Such a proportional pattern would be very unlikely if multiple distinct factors were acting directly on the items. ↩

-

In the common pathway model, any effects from genes to the indicators have to go through the latent variable, and therefore affect all the other indicators as well. Effects aren’t simply isolated. ↩

-

In the independent pathway model, there is no single latent variable through which all genetic or environmental effects must pass. Instead, genetic and environmental factors each have their own unmediated paths to the indicators. These factors can still affect multiple indicators at once, but they can also act on specific indicators only. ↩

-

PCA does not tell you whether factors are real, and technically it does not even find factors; it finds components. It is an atheoretical method that identifies the directions of greatest variance in the data. To test substantive hypotheses about how indicators relate to underlying constructs, you would instead use structural equation modeling. ↩

-

See Dynomight’s post: General factors of intelligence and physical fitness ↩

-

It depends on how homogeneous your indicators are. If the indicators measure heterogeneous physiological systems (strength, flexibility, endurance, reaction time), as is usually the case when people discuss a general athleticism factor, independent pathways should almost always fit better. If the test battery is more homogeneous, for example consisting only of endurance tests, common pathways may sometimes fit reasonably well. ↩